New research reveals hidden threat of seabed litter to UK marine biodiversity

16 October 2024

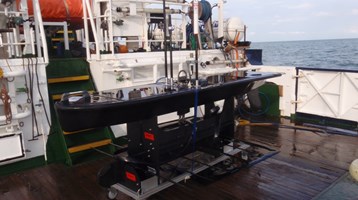

Scientists from the Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science (Cefas) have found a previously hidden threat to UK marine biodiversity: invasive species living on litter found on the seafloor. The findings present new challenges for the management and protection of the UK’s marine environment.

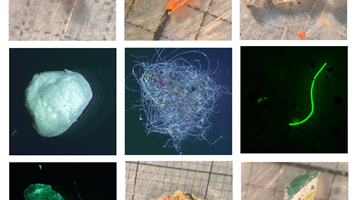

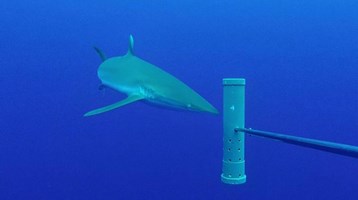

In the study, researchers analysed 41 pieces of plastic litter collected from the seabed off the coast of England and Wales. Among the specimens found were two species of non-native barnacles and four species of unknown origin. While invasive species entering the UK on floating marine debris has been well-documented, this is the first study to confirm their spread via seabed litter in UK waters.

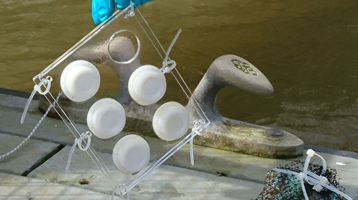

The findings suggest that seabed litter serves as an unexpected and often ‘unseen’ pathway for the spread of invasive species. Items like bleach bottles, plastic sheeting, and buckets were found to harbour these organisms, providing a unique settling platform to help their spread.

“This research exposes a new, hidden risk that seabed litter poses to our marine environment in the UK,” said Peter Barry, Marine Ecologist at Cefas and lead author of the study.

“Invasive species are remarkably resilient, capable of thriving and adapting to different environmental conditions, such as adverse weather, differences in sea temperature and food availability. However, their spread is often limited by the amount of suitable habitat available. What is concerning is that seabed litter seems to be providing a suitable home for these species, allowing them to get a foothold in British waters,” he added.

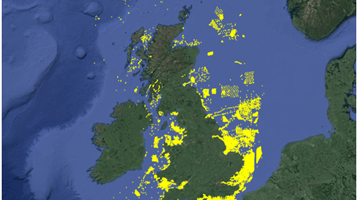

One significant finding was the presence of the Australian barnacle Austrominius modestus at depths of 27 and 32 meters off Northwest Wales and Northwest England. Typically found on the shoreline, their discovery suggests that either they were transported on litter from shallower waters or that seabed litter is providing a more suitable habitat at greater depths.

“The finding are a wake-up call for fellow scientists, policymakers and conservationists on the need to monitor seabed litter and ultimately eliminate it”, said Peter Barry.

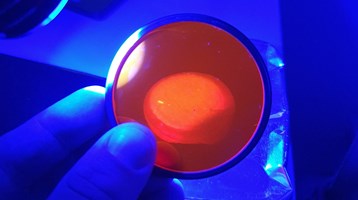

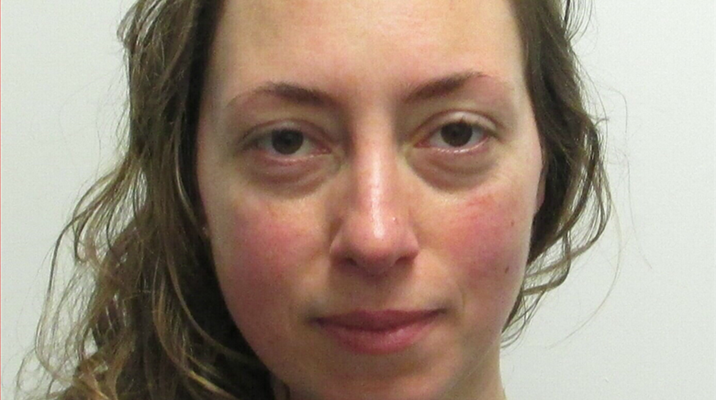

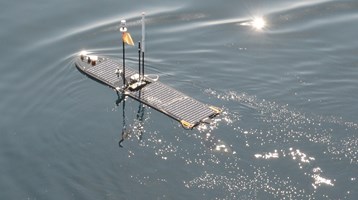

Cefas scientist holding plastic sheeting with barnacle species Solidobalanus fallax. Photo by Cefas

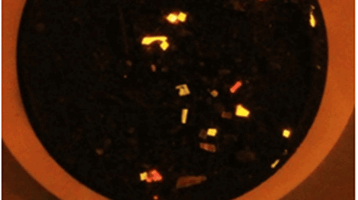

Austrominius modestus. Photo by John Bishop/Marine Biological Association

Recommendations and future research

Plastic litter has long been recognised as a major source of marine pollution, with devastating impacts on biodiversity. Invasive species, which are the second biggest threat to biodiversity after habitat loss, cost the UK economy nearly £1.9 billion annually. While floating litter has been identified as a vector for these species, seabed litter has not been widely recognised as a threat until now.

“A key challenge is that seabed litter is much harder to monitor compared to floating litter where the transfer of invasive species is well documented at typical ‘hotspots’ such as ports and marinas,” said Peter Barry.

Recommendations in the report include increased monitoring to better understand the link between litter types and potential hotspots, and different invasive species. This data could help identify areas most at risk, enabling more targeted conservation efforts, such as using data from seafloor litter as an early warning system in vulnerable locations.

The study also serves as a call to action for further research and new policy to prevent the spread of invasive species via seabed litter. Many international bodies, such as the United Nations Convention of Biological Diversity, do not recognise seabed litter as a pathway for invasive species.

Cefas is already expanding its research, analysing a further 150 pieces of seabed litter from different locations across the UK. Initial results have revealed two more invasive species, further supporting the theory that seabed litter is providing a novel habitat for these organisms.

“By collaborating with established monitoring programmes, such as the UK's Clean Seas Environmental Monitoring Programme, we’re gathering the data needed to truly understand the scale of this problem,” said Peter Barry. “This is just the beginning. Future research will be critical to informing conservation strategies and safeguarding the future of the UK's marine environment.”

Related to this article

Topic

Case studies

People

News

Further Reading

Working for a sustainable blue future

Our Science