New research highlights opportunities to transform UK marine monitoring

21 May 2025

- New research calls for an updated approach to how we track and assess nutrient pollution in UK seas.

- Advancing technologies like autonomous sensors and AI will transform our understanding of pollution and climate threats.

- It sets out five key innovations that offer an ambitious approach to managing and reducing the risk of eutrophication (water quality issues) in the UK’s coastal and marine waters.

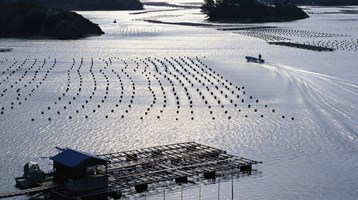

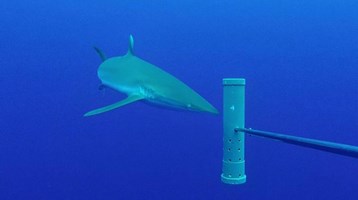

Coastal communities and marine wildlife could benefit from improved monitoring of nutrient pollution in UK waters following new research led by the Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science (CEFAS).

The study, published in Frontiers, reveals how the UK could drive innovation in integrated eutrophication monitoring approaches and advanced technology.

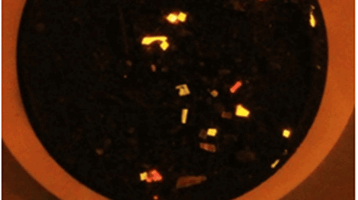

Eutrophication is the process where excess nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus enter waterways, causing harmful algal blooms and oxygen-depleted "dead zones" that damage marine ecosystems.

The comprehensive review, in partnership with the Environment Agency, Marine Directorate of the Scottish Government, Scottish Association of Marine Science, University of Plymouth and Tropwater, James Cook University, outlines five transformative opportunities to improve marine monitoring and adapt to the challenges of climate change and a changing marine environment:

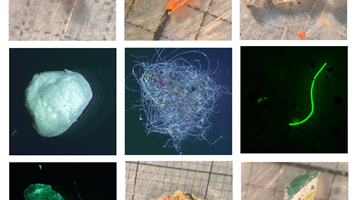

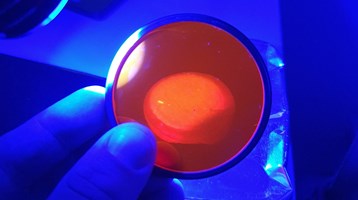

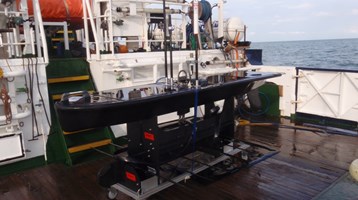

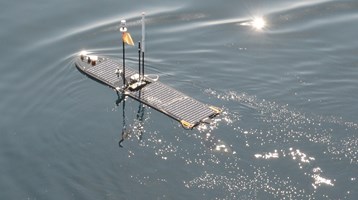

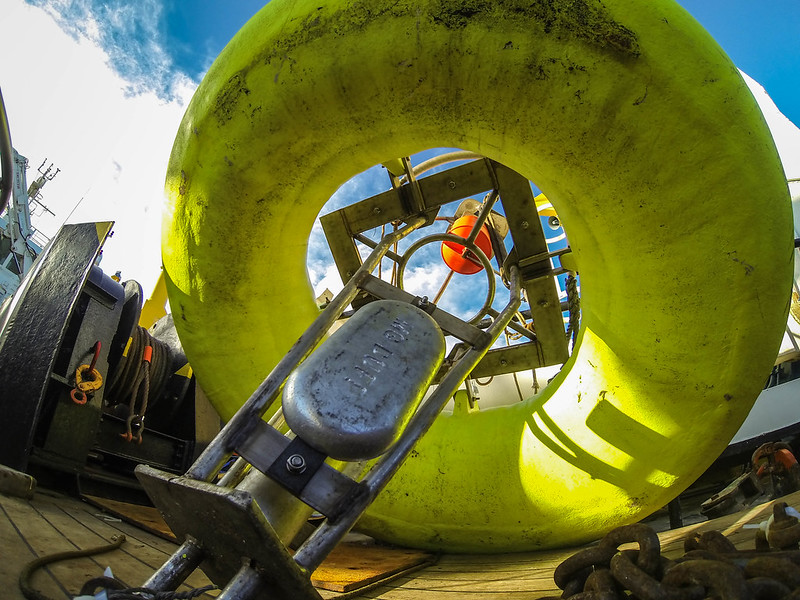

- Advance data collection: In addition to traditional methods like research vessels, continue to integrate data from emerging technologies such as real-time autonomous sensors, satellites, and AI, which enables more frequent and cost-effective monitoring. For instance, satellite data that detects tiny ocean particles—caused by plants, plankton, or pollution—is not yet routinely used in eutrophication assessments, despite its potential value.

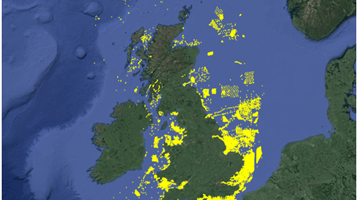

- Cross-boundary coordination: Breaking down barriers and improving coordination between agencies monitoring land, rivers and seas to create an integrated approach, rather than separate activities limited by political and geographical boundaries.

- Additional indicators: Collecting data on trends can help understand changes to water quality over time, improving the ability to predict future change, while indicators that measure the social, economic and environmental impacts of nutrient pollution can inform different management solutions.

- Understanding ecosystems: Monitoring sensitive organisms like plankton communities and fish populations to gain deeper insights into ocean health.

- Adapting to climate change: Recognising the interconnection between climate change and nutrient pollution to better predict and mitigate future impacts.

Professor Michelle Devlin, Principal Biogeochemistry Scientist at Cefas and lead author of the report said:

“The UK has a strong track record in assessing eutrophication and tackling nutrient pollution, leading to real improvements in water quality. But as our marine environment continues to change—and as data collection capabilities expand—our current definition of a ‘healthy’ marine ecosystem is increasingly outdated. We need to adapt our approach to how we define and monitor ocean health.”

"Future assessments must harness cutting-edge technology, break down barriers between monitoring agencies, and collect data that truly reflects the complex interplay between pollution, biodiversity and climate change. With a more comprehensive understanding, we can provide the right guidance to policymakers to protect marine ecosystems, balancing the needs of nature and society.”

Following Britain's exit from the EU, the UK government's Marine Strategy now serves as the main framework for coordinating legislation and monitoring in coastal and marine waters across the four UK Administrations.

The report calls for government agencies responsible for monitoring coastal and marine waters in the UK to work collaboratively to innovate and improve monitoring programmes, alongside better engagement with river trusts, conservation groups, farmers, water operators and communities.

This research supports the government's Water Bill, which sets out a commitment to cleaning up Britain's waterways and strengthen regulation of water companies.

Notes to editors:

- This work was funded under Defra’s’ 3 year marine Natural Capital and Ecosystem Assessment (mNCEA), which aims to provide policymakers with the evidence, tools, and guidance to integrate marine natural capital approaches into policy and decision making for marine and coastal environments.

- Eutrophication assessments under the recent UK Marine Strategy Part 2 include the coastal assessments carried out under Water Framework Directive (England and Wales) and Water Environment Regulations (Northern Island) and the coastal and offshore assessments carried out under the OSPAR.

- Cefas is responsible for monitoring plumes and monitoring coastal and offshore waters around the UK and leading on UK’s marine Strategy.

- Environment Agency (EA), Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (DAERA), Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA), Agri-Food and Biosciences Institute (AFBI) and Natural Resources Wales (NRW)are all responsible for monitoring under the UK’s Water Framework Directive in the UK’s estuaries and coastal waters

- The pelagic data collected by the four agencies also contributes to biodiversity assessments required under OSPAR and the UK Marine Strategy (UK MS).

- Targets for measuring nutrient pollution and achieving Good Environmental Status (GES) in our seas are set under the UK’s Marine Strategy and reviewed every 6 years. GES aims to protect the marine environment, prevent its deterioration, and restore it where practical, while allowing sustainable use of marine resources.

Related to this article

Topic

Case studies

People

News

Further Reading

Working for a sustainable blue future

Our Science